SAN DIEGO – And to think, up until last week, I would have said that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh was painfully boring with a confirmation process to match.

What do I know? Scandals are never boring. Still, as a proud American who hates to see our institutions sullied, give me boring any day.

The Kavanaugh proceedings have taken a detour into the sewer, which explains the stench.

Senate Democrats are trying to take out this nominee, for the unpardonable sin of having been nominated by President Trump. And a lot of what has happened over the past several days does not make their side look pure and wholesome.

Consider:

- The fact that the accusation of sexual misconduct was initially made anonymously.

- The fact that Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California — who learned of the allegation several weeks ago — never mentioned it during the hearings or in a private meeting with Kavanaugh.

- The fact that the man who was reportedly with Kavanaugh during this alleged assault says it never happened, and that he never witnessed the nominee being disrespectful to women.

None of this helps the Democrats in their crusade to kill the Kavanaugh confirmation by any means necessary.

To get here, we took a dark and dangerous road.

But here we are nonetheless. And, just days before the scheduled Senate vote on Kavanaugh’s nomination, we’re facing a barrage of questions. For instance, do we believe what she said, or what he said?

And: Even if Kavanaugh did — as a 17-year-old who had too much to drink — everything that she said, should it doom Kavanaugh’s nomination?

And also: What about that article of faith among liberals that says people can change?

Barack Obama admitted to using cocaine. George W. Bush had a drinking problem. Bill Clinton said he smoked marijuana but apparently incompetently since he claims he didn’t inhale.

American voters gave them all a second chance — and, ultimately, two terms in office.

I could list the moral failings of the current president that his supporters — including on the religious right — are all too willing to forgive, but I don’t have the word space.

Which brings us to this question: Is the moral standard for a Supreme Court justice higher than it is for the leader of the free world?

And this one: What’s the standard for a U.S. senator? The late Edward Kennedy left the scene of a car crash off a bridge on Chappaquiddick Island in 1969, where a young woman died. Kennedy served for another 40 years.

Why? Because, as they say on the left, people change.

But apparently not Supreme Court nominees put up by Republicans. They aren’t people, too?

And yet, at the same time, Kavanaugh has not done himself any favors with the way he has responded to his name being dragged through the mud. How he reacts now, as a grown man, says more about his character than what he may have done as a teenager. So far, not so good.

The accuser is Christine Blasey Ford, a California psychology professor who says that she recently passed a lie-detector test about the incident and that she told a marriage counselor about it in 2012, though she didn’t mention Kavanaugh by name back then.

Why would she? How many people knew who Brett Kavanaugh was in 2012?

There is no upside for Ford. Whether the allegation is true or not, her life will never be the same. Ask Anita Hill.

To all this, Kavanaugh says coolly: It never happened. That’s it.

His handlers have also released a letter signed by 65 women who claim that they knew the nominee in high school and he never behaved this way.

The letter is a ridiculous tactic that proves absolutely nothing, by the way, except perhaps that Kavanaugh didn’t behave badly with any of those 65 women.

The nominee must do better. If you’re innocent, you don’t parse your words. You holler! It’s time for a Clarence Thomas “high-tech lynching” moment where Kavanaugh goes back before the Senate Judiciary Committee — as he is scheduled to do on Monday, along with Ford — and says that, as the father of two young girls, he is outraged that the opposition would sink this low. This is your name, Judge. Let’s hear the holler.

Otherwise, I’ll be inclined — along with what I’m sure will be many other Americans — to discount what he said and believe what she said.

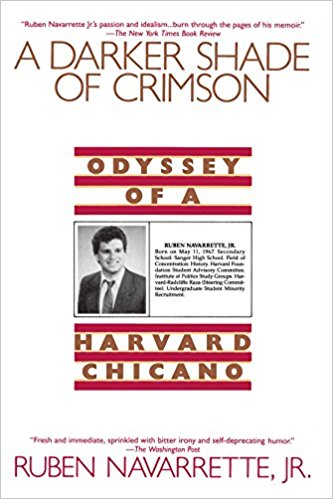

Ruben Navarrette has a daily podcast, “Navarrette Nation,” and may be contacted at ruben@rubennavarrette.com.

© 2018, Washington Post Writers Group