Mesmerized by Meghan McCain’s tearful sendoff on Saturday for her father, Senator John McCain, I spent the rest of the weekend thinking about eulogies.

I wondered: What makes a good eulogy? What purpose do they serve? Are they for the dead — or the living?

On a personal note, I wondered: What kind of job have I done the half dozen times I’ve stepped up to eulogize loved ones? Did I manage to do justice to the legacy of those who meant so much to me, as I tried to summarize an entire life in just a few minutes? And, one day, what kind of eulogy would I like friends and family members to deliver on my behalf?

Most of all: How do I want my kids to sum up my time on Earth? When my time comes, will my kids know me well enough to tell the world who I was, what I stood for, what values I held dear, what principles I cherished and how I tried to live my life? Will they be able to say what defined me, set me apart, and made up what my own father refers to as a person’s “core?”

I’ve thought about eulogies before. I’ve contemplated how there are — as New York Times Columnist David Brooks puts it — “resume virtues” and “eulogy virtues.”

The last time I thought about these things was in May, when 92-year-old former First Lady Barbara Bush — a beloved public figure if ever there was one — went to be with the Lord after a life lived gracefully. Bush said that her life’s greatest legacy was “the children and the grandchildren.”

When my day arrives, I hope that at least one of my kids steps up to bid me fond adieu. Or, in my family, a hearty “adios”.

To prepare, I hope they recall Meghan McCain’s tribute to her dad, which was really one of the most beautiful sendoffs we’ve ever seen. It’s the new gold standard for public figure eulogies.

What made Meghan McCain’s words so powerful, and so memorable, was that they gave us a peek into one of the most important of the senator’s roles: that of father. Those were words written by a daughter about her father — a father that she, perhaps reluctantly, shared with the world. That was a part of John McCain that was known to only seven people — his sons and daughters.

Days later, a daughter’s words still rattle around in my head and bring tears to my eyes:

“My father is gone. John Sidney McCain III was many things. He was a sailor, he was an aviator, he was a husband, he was a warrior, he was a prisoner, he was a hero, he was a congressman, he was a senator, he was a nominee for President of the United States. These are all of the titles and roles of a life that’s been well lived. They’re not the greatest of his titles nor the most important of his roles. … My father was a great man. He was a great warrior. He was a great American. I admired him for all of these things. But I love him because he was a great father.”

Life gets complicated. Relationships get frayed over time. Those who once thought you hung the moon eventually see your flaws.

But to have even one of your children say such things about you at the end of your days is an incredible honor.

Meghan remembered her father “kissing the hurt when I fell and skinned my knee,” and making her get back on a horse after a broken collarbone. “Nothing is going to break you,” McCain told his little girl. Obviously, listening to her, nothing has.

I remember when my 13-year-old daughter, Jacqui — named after Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who noted, if you mess up the raising of your kids, nothing else you accomplish in life matters — was just starting preschool. One day, I was juggling the demands of family and work, and probably falling short on both counts. But perhaps my little girl could see I was trying. She grabbed my arm, looked me in the eye, and said: “You’re a good daddy.”

I’ve had a good life, with my share of accomplishments and accolades. But, at that moment, I was three feet off the ground.

Given an extraordinary life lived well, John McCain has much to be proud of. In good days, and through hard times, he had an intimate relationship with something he cared a lot about: the concept of honor. And as he went to his rest, he was showered with the love and respect of a grateful nation.

Still, as the maverick looked down from heaven upon his grand sendoff, what should have given him the most satisfaction were the loving words of a grateful daughter.

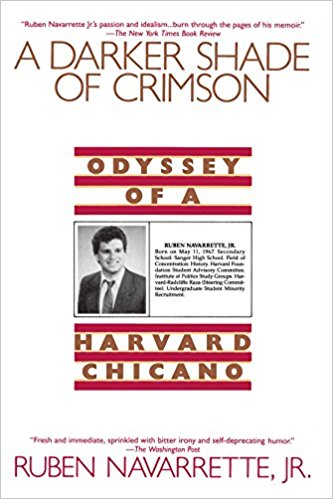

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”