One thing that was missing from the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings was something that is tough to find on the Potomac: ol’ fashioned common sense.

For instance, as someone who watched most of the hearings, I don’t think I ever heard any member of the Senate Judiciary Committee or the so-called elite media make the point that was probably running through the minds of average Americans: Human beings are usually completely different people at 17 than they are at 53.

As is so common in today’s politics, much of the debate — about whether to believe Kavanaugh or the woman who accused him of sexual misconduct as a teenager, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford — happened at the extremes with not much room for nuance.

Half the country seemed to think Kavanaugh was not capable of such misbehavior as a teenager because he was now such an upstanding man. The other half of the country thought Kavanaugh was no doubt capable of misconduct in his teens and that he was likely still engaged in such behavior.

Both sides were painted into corners. Those on the Right couldn’t concede that Kavanaugh had, at any age, ever done anything wrong. Those on the Left couldn’t admit that, regardless of what he was accused of doing as a teenager, he turned out all right.

Not me. I’m blessed to not live on the Right or the Left. And, that’s just as well since I often cannot tell them apart.

So, I had no trouble believing both narratives: that Kavanaugh was, as a teenager, an entitled train wreck who drank too much, and may have on occasion acted inappropriately with girls; and that he has, for the last three decades, lived an exemplary life marked by public service, devotion to family, and a genuine commitment to God and the Catholic Church.

Those two ideas can co-exist peacefully on the same plane. That is, they can both be true. It’s not either / or — despite the best efforts of politicians frame most public debates in precisely those narrow terms.

And the best way to understand this fact is to listen closely to what Kavanaugh said to supporters at a recent White House ceremony intended to celebrate his confirmation.

In his remarks, the newest justice on the Supreme Court made his case as plainly as anyone could by giving due credit to the three people who saved him — his wife and his daughters.

“My daughters, Margaret and Liza, are smart, strong, awesome girls. They’re in the middle of fall lacrosse, looking forward to the upcoming basketball season. I thank their teachers for giving them the day off tomorrow so that they can come watch two cases being argued at the Supreme Court.

“My wife Ashley is a proud West Texan from Abilene, Texas. Graduate of Abilene Cooper Public High School, University of Texas in Austin. She’s the dedicated town manager of our local community. She’s got a deep faith. She’s an awesome mom, a great wife. She is a rock.

“I thank God every day for Ashley and my family.”

As well he should. It’s hard to imagine the stress that this average American family has endured over the last several weeks. I’m sure that, at various times, both the nominee and his wife were tempted to walk away from the entire process, and withdraw from consideration.

That would have been a mistake, and a big loss for the country and the judiciary. But it would have been, for most Americans, totally understandable. Most of the credit for pulling us back from the brink, I’m sure, goes to Ashley, who stood by her husband in his hour of need.

The Brett Kavanaugh story is not about allegations of sexual assault, or teenagers who drink too much, or crude jokes scribbled in high school yearbooks. Nor is it about opponents overplaying their hand and displaying their hypocrisy, as they try to destroy the life of a fellow human being with no real evidence that he did anything wrong.

The Brett Kavanaugh story is about salvation and redemption and second chances.

It’s about a theme you find throughout the Bible, and in the lyrics of a glorious Christian hymn penned by English poet John Newton back in 1779. The words go like this:

“Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see…”

Americans understand this idea. Christians put faith in it. Most people have no trouble grasping the concept that we can be one person when we’re single and alone — and a completely different person after we get married and have children. That’s how life works.

It’s common sense. Which goes a long way toward explaining why this critical aspect of the Kavanaugh hearings eluded so many people who make their living in politics and media.

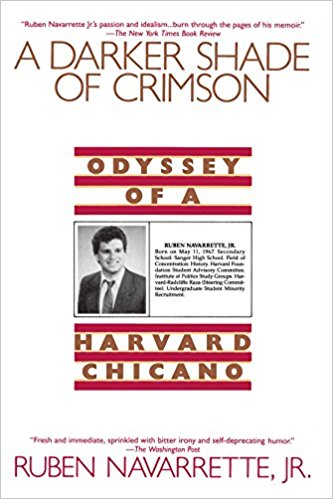

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”