Now that John McCain has been laid to rest, it’s worth paying tribute to his special relationship with Latinos — especially Mexican-Americans in the Grand Canyon State.

The Arizona senator “got” Latinos, and Latinos “got” him. In ways the national media never understood during his presidential campaigns, McCain and la comunidad were blood brothers.

I saw the bond up-close in the late 1990s, as a reporter and metro columnist at the Arizona Republic. Even in a city that was then about 25 percent Latino, the number of Latino bylines at the paper could be counted on two hands. I got grief from whites who thought I was too Latino and Latinos who thought I was too white. In fact, my Latino colleagues and I took so much abuse that the reader advocate playfully nicknamed us “the pinatas.”

I think McCain figured out pretty quickly that my job was no fiesta, and so he reached out with a compliment or an encouraging word — something he would do repeatedly over the years.

McCain & Latinos. What a pair these two rascals made. They spoke the same language: God, family, country. They had the same values: honor, sacrifice, hard work. They dearly loved this land, and they didn’t hesitate to defend it. And they had the scars and medals to prove it.

For McCain, I bet what drew him to Latinos had something to do with what former President George W. Bush said in the eulogy he gave for his rival for the 2000 Republican nomination.

“There was something deep inside him that made him stand up for the little guy, to speak for forgotten people,” Bush said.

Poorly served by both parties, and lost in a black-and-white paradigm that has no room for them, Latinos are the quintessential little guy forgotten by the powerful and influential.

Yet McCain never forgot them. And they never stopped appreciating him, routinely giving him more than 60 percent of their vote in his Senate campaigns.

Twice, McCain was recognized for his service to the Latino community by the National Council of La Raza. In 2008, it was council President Janet Murguia who herself noted this fact when introducing McCain at the council’s annual conference in San Diego. I was in the room. Ten feet from where I was sitting, as McCain took the stage, a small group of gray-haired Latino veterans with their military caps on stood at attention and saluted.

As for what drew Latinos to McCain, it was his military service and his heroism as a prisoner of war.

You love your country so much that you send your sons and daughters to defend it, and sometimes all you get back is a folded flag and a 21-gun salute, “on behalf of a grateful nation.” The tio who died at Iwo Jima. The son we lost during the Tet Offensive. The cousin who took his last breath outside Kabul. Latinos know this story by heart.

Take it from the padrino to McCain’s son, Jimmy, Arizona businessman Tommy Espinoza. Padrino means “godfather.” A padrino is the person you select to raise your kids if something were to happen to you.

That person for the McCains was Tommy Espinoza. A friend and McCainiac for 30 years, Espinoza is also a Mexican-American Democrat who once headed up a Phoenix-based Latino advocacy group called “Chicanos Por La Causa.”

“He would say, ‘You know what? I can’t believe that these families that come from another country, from Mexico, from Central America to work, cutting our grass, feeding us, bringing in the labor force that we need, and now we turn on them?’ “

As he left the podium, Espinoza looked at the flag-draped casket before him and bid farewell to his compadre.

“My dear friend, vaya con Dios,” he said, as he made the sign of the cross.

While running for president in 2008, McCain spoke to me from the campaign trail. He reflected on his support from Latino voters. He told me it was an honor to represent “so many patriotic and great, wonderful Americans who are the heart and soul of the country.”

No, Senator. With you so often in our corner, the honor was ours.

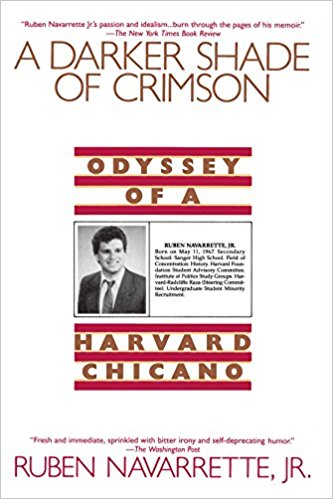

— Ruben Navarrette is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group.