We should wonder what Americans learned from the divisive and depressing 2016 election.

Given the results of the recent midterm elections, the answer appears to be: Not much.

Two years ago, on this site, before votes were cast in that earlier election, I wrote: “Our new president, and his or her administration, also has to take on as its primary goal the theme of reconciliation. … The old saying goes: ‘To the victor goes the spoils.’ But this time, after this wacky and wild election is over with, the victor will also get something much more profound: The responsibility to unite what has been divided and mend what is broken.”

After the election, I observed: “The United States seems more divided now than it was before the election. Tempers are short. Feelings are hurt. Emotions are frayed. It’s no longer possible to agree to disagree. Everything is accompanied by a moral judgment. Motives are immediately questioned. There is little respect and no room for nuance. Overall our national discourse has gradually become more polarized, more personal, more presumptuous and more petty.”

Now, two years later, with the midterms behind us, the bad news is that our national discourse — that is, what we have to say to one another and how we talk to one another — is still too polarized, too personal, too presumptuous, and too petty.

In fact, all that seems to be getting worse. The theme of the midterm elections was not “Hope and Change” or “Make America Great Again.” It was “Deception and Fear.”

Democrats and Republicans are both claiming victory, and both parties have reason to celebrate. Democrats turned out their voters and reclaimed control of the House of Representatives. Republicans turned out their voters and strengthened their grip on the Senate. Democrats won some key races, and Republicans won other key races.

In fact, if you’re non-partisan and a fan of representative democracy, it was a glorious election.

But, at the same time, we should acknowledge that much of the results in individual races came about through deception. Anyone who follows politics knows that elected officials, and those running for elective office, are often quite comfortable spreading misinformation, misleading voters, and shading the truth.

But what is not often talked about is that most of the misleading goes on between the politicians and their supporters.

For instance, Democrats only wanted to talk about health care, and they had no interest in confronting immigration — or the migrant/refugee caravan that is now headed for the U.S.-Mexico border. If they had to discuss immigration, they would — sooner or later — have to navigate the messy divide between blue-collar workers who want less immigration and Latinos who wouldn’t mind more of it. They would have to mislead one group, or both.

Meanwhile, Republicans only wanted to talk about immigration and the caravan. If they had to discuss health care, they would — sooner or later — have to navigate the messy divide between those Republicans who voted to keep the Affordable Care Act (aka “Obamacare”) because they thought repealing it would do more harm than good and the outraged conservative voters who put Republicans in office specifically to repeal that legislation.

In both cases, and for politicians in both parties, the only way to walk safely through those respective minefields is through deception. They can’t afford to tell the truth.

And then there was the fear factor. Democrats drove turnout and scared up votes by convincing their supporters that Republicans were going to take away their health care and let everyone get sick. Across the street, Republicans drove turnout and scared up votes of their own by convincing supporters that Democrats were going to open up the borders and let everyone in.

Guess what? In both cases, it worked.

No surprise there. Fear usually does work. That is a lesson that goes back centuries. History shows us that tyrants and dictators and madmen did more harm with fear than with armies, weapons, and warfare.

You can always try to counter fear with facts. That is to be expected. But don’t assume much will come of that. Fear doesn’t usually listen to facts. And, these days, it is stone-cold deaf to them.

So we didn’t learn much from the 2016 election, and that led us to the 2018 election. What can we hope for in 2020?

In the end, it’s all about being better. We should all aspire to something better. Americans have to do better. We have to communicate better, and show more respect to one another. We need to engage in the political system in better and more productive ways. Our elected officials need better ways of addressing us, and they should try to be better people. And, most of all, we should demand better of them, of ourselves, and of this great country.

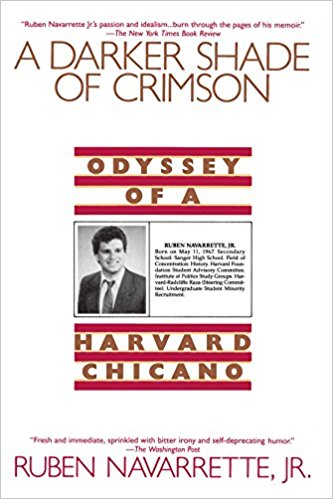

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”