In these strange times, Mexicans — and by that, I mean the whole extended familia: Mexican legal residents, Mexican-Americans, naturalized Mexican-born U.S. citizens, and undocumented Mexican immigrants — don’t have many friends, allies, advocates and defenders who are willing to stick their neck out and risk their livelihoods on our behalf.

Tragically, there is one less such person now that Anthony Bourdain is gone. The beloved and celebrated chef and writer — who became an unlikely television star thanks to his CNN show, “Parts Unknown” — apparently committed suicide last week in Paris.

Bourdain was an outspoken defender of, and advocate for, Mexican immigrants. He was not shy about standing up to bullies. He took on racists who would just as soon deny the many contributions of immigrant workers to, for instance, the restaurant industry because it doesn’t fit their narratives that immigrants are takers who are bankrupting the United States. He knew the truth. And he would write it, say it, and share it on social media — without apology or reservations.

Bourdain was a friend to Mexico, and to Mexicans, when they were most in need of support. It often feels as if our friends south of the border, and their distant relatives north of the border, are the last group of people on Earth that despots and demagogues can mistreat and malign with impunity.

President Trump traveled all the way to Singapore to broker a deal with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, whose country was not so long ago considered part of the so-called Axis of Evil.

Meanwhile, in this hemisphere, consistent with a bizarre policy of treating our friends and neighbors in an unfriendly and un-neighborly manner, Trump and members of his administration continue to treat Mexico — a trusted ally and trading partner — with utter disrespect, bordering on contempt.

But while Bourdain stood by Mexico and Mexicans, the misery of it is that they didn’t the chance to return the favor.

I’m a writer. I’m also a foodie. So believe me when I tell you that writers who are also foodies come in two varieties: Those who envied, admired, and respected Anthony Bourdain — to the point where they wanted to be Anthony Bourdain; and those who have trouble telling the truth.

Who could blame us for envying him? Here you had someone who was paid to travel the world, stay in the best hotels, eat fantastic food, meet interesting people, and tell good stories.

Where do I sign up?

Now the 61-year-old’s sudden and shocking death leaves us with a huge and uncomfortable question: How could it be that someone who had a life that so many people wanted to have apparently didn’t want it himself?

Last year, I was asked by Bourdain and his production company in New York to go into the avocado groves and mandarin orange fields northeast of San Diego and find out what would happen if America deported every illegal immigrant. Bourdain thought it would topple the restaurant industry and literally leave Americans wondering where their next meal was coming from.

I took the assignment, grabbed my notepad, and headed out to the fields. What I saw there taught me that Bourdain was right — that the U.S. agricultural industry is now completely dependent on illegal immigrant labor and that the workers who feed the country deserve our nation’s appreciation and respect.

Bourdain paid his respects by speaking truths like this:

“Americans love Mexican food. We consume nachos, tacos, burritos, tortas, enchiladas, tamales…in enormous quantities. We love Mexican beverages, happily knocking back huge amounts of tequila, mezcal and Mexican beer every year. We love Mexican people — as we sure employ a lot of them. Despite our ridiculously hypocritical attitudes towards immigration, we demand that Mexicans cook a large percentage of the food we eat, grow the ingredients we need to make that food, clean our houses, mow our lawns, wash our dishes, look after our children. So why don’t we love Mexico?”

What a good question, even if the answer will never come.

Or this: “As any chef will tell you, our entire service economy — the restaurant business as we know it — in most American cities, would collapse overnight without Mexican workers. Some, of course, like to claim that Mexicans are ‘stealing American jobs.’ But in two decades as a chef and employer, I never had ONE American kid walk in my door and apply for a dishwashing job, a porter’s position — or even a job as prep cook. Mexicans do much of the work in this country that Americans, probably, simply won’t do.”

Preach it brother. I’m tempted to say that Anthony Bourdain was an honorary Mexican. But he was more than that. He was our compadre. He was familia. And he will be missed as such.

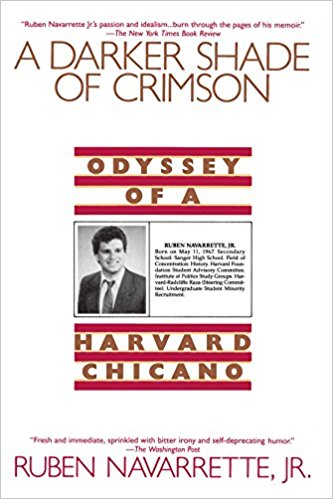

Ruben Navarrette, a contributing editor to Angelus News, is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a Daily Beast columnist, author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano,” and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.”