I missed the Bobby Kennedy story. Yet, inexplicably — as a student of history, as a Mexican-American, as part of a family that worshiped Camelot, and as a Catholic — I’ve spent the last 50 years missing Bobby Kennedy.

I was only 13 months old on June 6, 1968, when Robert Francis Kennedy was shot and killed at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, where the Democratic candidate for president had gathered with supporters to celebrate his winning the California primary. A son of Hyannis wealth and privilege who sat at many tables — Harvard, Senate aide, helping elect his brother president, fighting the good fight as Attorney General, serving as U.S. senator from New York, running for president — took his last breath on the floor of a hotel kitchen, holding the hand of a poor Mexican dishwasher who gave him a rosary.

Yet what matters most about the fellow whom my grandmother used to call “El Bobby” was not how he died but how he lived.

Consider what United Farm Workers Vice President Delores Huerta — who was at Kennedy’s side that night in Los Angeles — said about him. Huerta recalled that, while other politicians would go into Mexican-American neighborhoods and tell people what was best for them, Bobby would ask two questions: “What do you need?” and “How can I help?” Then he listened.

When speaking with Mexican-American voters or lending support to farm workers, he might stop to touch a child’s cheek in a genuine show of affection.

Huerta noted that, while Mexican-Americans admired President John F. Kennedy, their bond with the younger brother was stronger. “With Bobby, it was like he was ours,” she said.

From everything I’ve read, watched, studied and heard over the years about the connection between Bobby Kennedy and Mexican-Americans, it seems that — for many in my community — it wasn’t just that Bobby was ours. It was that he was us.

RFK Biographer Jack Newfield described Bobby as “more Irish and more Catholic” than his brother. He didn’t have all the answers. He was always searching, challenging, questioning. He thought about becoming a priest. And, as he traveled, he was never without the protection of his medal of St. Christopher.

Even as a Kennedy, life did not always go his way. He struggled in school, and he had to hit harder in football because he was so small. He was comfortable in the shadows, the strategist behind the scenes making others look good. He was easily overlooked or ignored in a large brood. He knew what it was like to struggle, to be picked on, to be chosen last.

Most of all — in the dark, grief-shrouded days after November 22, 1963 — Bobby Kennedy knew what it was like to have your heart broken and experience, often against your will, what his favorite Greek philosopher, Aeschylus, called the “wisdom” that comes from “pain that cannot forget.”

This is all familiar terrain to Mexican-Americans. And it helps explain why Bobby was our most beloved Kennedy.

My favorite Bobby moment? It happened on my home turf, in California’s San Joaquin Valley three months before he died.

On March 10, 1968, Kennedy quietly made a pilgrimage to the farm town of Delano to attend a Catholic Mass. There, he helped Cesar Chavez break a 25-day fast. Kennedy told those who had gathered, “When your children and grandchildren take their place in America, going to high school and college, and taking good jobs at good pay, when you look at them you will say, ‘I did this, I was there at the point of difficulty and danger.’ And though you may be old and bent from many years of hard labor, no man will stand taller than you when you say, ‘I was there. I marched with Cesar!’”

My favorite speech? It was the one Bobby delivered on June 6, 1966 at The University of Cape Town in South Africa. There, he told an audience of college students:

“Few men are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change the world which yields most painfully to change. I believe that in this generation those with the courage to enter the conflict will find themselves with companions in every corner of the world.”

Maybe it was the Irish, or the Catholic, or the fact that he could — despite his wealthy and privilege — identify with the dispossessed and the downtrodden. But for whatever reason, Robert Francis Kennedy found the courage to enter the conflict.

On the 50th anniversary of his trip home, that’s worth remembering — and honoring.

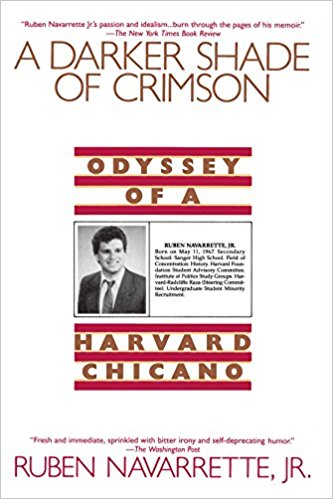

Ruben Navarrette, a contributing editor to Angelus News, is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a Daily Beast columnist, author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano,” and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.”