SAN DIEGO – Today, I begin a new chapter in my career as a journalist. For the first time in three decades, I’ll have to face the daunting task of writing and talking about a world of politics that doesn’t have John McCain in it. I can’t conceive of it. Frankly, I dread it.

I think of McCain’s path — from the U.S. Naval Academy to the Hanoi Hilton to 36 years in the House and Senate to two presidential campaigns – and how well he handled it all.

Then I look at the newer models that make up America’s crop of Politicians 2.0. I see elected officials who break promises, flip positions, betray constituents, lie to supporters and work magic tricks worthy of Houdini to get out of scrapes.

In fact, when their backs are up against the wall, some will even sacrifice their loved ones on the altar of self-preservation.

Last week, after being indicted on federal corruption charges for allegedly misusing campaign funds on trinkets like a family trip to Italy, Rep. Duncan Hunter Jr., R-San Diego, blamed the whole thing on his wife to whom he had given power of attorney. Hunter – a former Marine who served in Iraq and Afghanistan — may have been an officer, but obviously he’s no gentleman.

McCain — who spent 5 ½ years as a prisoner of war after being shot down by the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War — would often joke that he had built his career backwards. “I was in prison, and then I went into politics,” he said.

Hunter seems headed in the other direction.

I think of all that, and then I think of McCain. And I am left with the most anguishing sense of inadequacy — and loss.

Now McCain has gone to his rest at 81 after losing his last fight — a year-long battle against brain cancer. And, in politics, all that’s left is the dregs.

I knew McCain for 20 years. And yet I might not have ever met him at all had I not packed my belongings into my Jeep Cherokee in the summer of 1997 and moved to Phoenix — despite not knowing a soul in the Grand Canyon state — to take a job as a reporter and metro columnist at the Arizona Republic.

As I try to nail down what made McCain special and attempt to explain the huge footprint he left on the American political scene at the end of one century and the beginning of another, my heart swells and my mind races. In the end, all I can come up with is honor, Cambridge (Massachusetts), lettuce, nachos, and my mother.

Honor: This was the word that brought us together. In late 1998, I read a news article in the Republic about McCain’s phenomenal level of support from Latinos in his Arizona Senate races — upward of 65 percent. Everyone was talking about how Gov. George W. Bush was getting 44 percent of the Latino vote in Texas, and here was McCain outdoing that by 20 points. In the article, McCain described the Latino support as his “honor.”

In 1999, I wrote a column about McCain and Bush facing off for the GOP nomination in the 2000 presidential campaign. I ended it this way: “One imagines that someone who spent 5 ½ years in the Hanoi Hilton does not take lightly a word like honor.” McCain read the column and found a classy, back channel way of expressing his gratitude.

Cambridge, MA: It’s the winter of 1999, and I’m standing in the well of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, where McCain — who was then running for the 2000 Republican nomination for President — had just delivered an inspirational speech to students. A young man in the audience headed for military service got a round of applause when stood up and told McCain that he would be “proud” to serve under such a Commander-in-Chief. I approach McCain with a smile and a gift — a Kennedy School cap.

He sees me, says: “Ruben! My God, how are you? Good to see you, Man!” Standing next to me is my professor, David Gergen, who sees the whole thing. Then, McCain — shaking my hand vigorously — turns to Gergen and sings my praises. Later, Gergen would tease me in front of my entire class. “The gushing! It was embarrassing,” he told my classmates. Everyone had a laugh at my expense.

Lettuce: As an outspoken champion of comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for the undocumented, McCain came under fire from members of his party — conservative Republicans whose understanding of the realities of the immigration debate was one taco short of a combination plate. Protesters would challenge him on his claim that immigrants — no matter how they got here — did jobs that Americans wouldn’t do.

Not one to back down from an argument, McCain at one point made protesters a personal offer. He would tell them: “I’ll pay you $50 an hour to go to Yuma and pick lettuce — for the whole season! Will you do it?” He got no takers. Maverick 1, Critics 0.

Nachos: McCain’s rational approach to immigration made other Republicans look bad. Few looked worse than Rep. Tom Tancredo, the openly nativist GOP Congressman from Colorado who also sought the GOP presidential nomination in 2008. McCain was likely thinking of Tancredo when — during a phone interview in October of that year, just before he would lose to Barack Obama — he told me this: “During the immigration debate, it’s very clear that a lot of the language and rhetoric that was used (by Republicans) made Latino citizens believe that we were anti-Latino.”

And this: “Throughout our history, we have always had people who stoked nativist instincts.” At one point, during the primary, all the GOP hopefuls were in a Mexican restaurant in Las Vegas before a debate. I asked McCain if there was any truth to a story floating around that Tancredo had taunted him over his support from Latinos. “Yeah,” McCain said, “we were in a restaurant and he just sent over a plate of nachos. What do you say to something like that? I just said, `Thanks very much.’”

My mother: My mom is a South Texas, Rio Grande Valley lifelong Democrat who, at 21, had her heart broken by the national tragedy that unfolded in Dallas on November 22, 1963. She went all in for Hillary Clinton in both 2008 and 2016 — the t-shirt, the book, the whole nine yards. In fact, she has only voted for one Republican in her entire life. In the 2008 primary, she was — as a child of the Vietnam era — so moved by McCain’s personal story of having turned down early release from captivity rather than allow the North Vietnamese a propaganda victory that she went so far as to change her party registration so she could vote for him. All of a sudden, my mom is the only Republican in a Democratic household.

A few weeks after McCain lost the nomination to George W. Bush, I asked my mom if she was equally excited about casting a vote for Bush against Al Gore. “What do you mean?” she asked. “I’m not a Republican anymore. I changed back to Democrat.” Dumbfounded, I asked: “What?” She explained: “Look, I became a Republican to vote for John McCain because he’s a hero. But, George Bush, no, no. That’s not the same man. There’s a big difference between the two.” I’ve long suspected my mom would be better at my job than I am.

John McCain was an American original, and we won’t see the likes of him ever again. We won’t be that lucky.

His life was a paradox: What made him so big was that he knew he was small. Next to his fellow prisoners, his country, his family, and now as he stands before his God, he was always clear that he owed the debt, not the other way around. People speak of his courage, but what made him special was something lacking in a lot of our elected officials: humility, wisdom, and perspective.

Yet, McCain was not perfect. He did not cover himself with glory when, facing a tough re-election against a right-wing cartoon figure in 2010, he endorsed the racist Arizona immigration law. The Latinos who loved him deserved better.

The last time we spoke was back in 2008, during that phone interview before his loss. “Thank you, Ruben,” he said at the end of it. “I’ve always admired you…”

God bless you, Senator. You’ve earned your rest. You served with honor. I didn’t always agree with you. I wasn’t always happy with you. And I wasn’t always proud of your decisions.

But I always admired you.

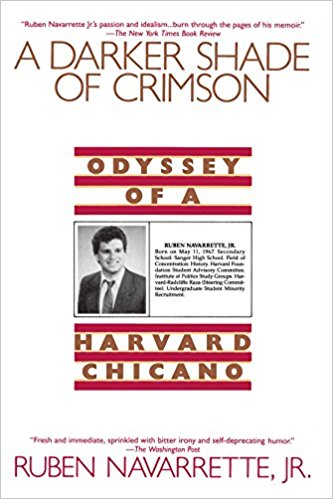

Ruben Navarrette — a contributing editor to Angelus News — is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a Daily Beast columnist, author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano,” and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.”