During my freshman year in college, I took a course in political philosophy. My classmates and I studied the writings of Aristotle, John Stuart Mill, John Locke, Immanuel Kant and others. Every week we’d be presented with a moral quandary, and we’d be asked to explain how we thought it should be resolved, using the philosophies available.

I remember one scenario in particular. There are three men adrift on a lifeboat in the ocean, far away from land and without any food. It is clear that they won’t all survive, but two of them might have a chance if they resort to cannibalism and devour the third.

The question: Is it justifiable for the two strongest men to kill and eat the weaker one?

Before I could contemplate an answer, I suddenly came to the realization that the question was moot. I heard a voice in my head — from my hometown 3,000 miles away, from my childhood.

It was telling me that the whole premise of this exercise was absurd, and the outcome unthinkable. It wasn’t a matter of what could be justified. It was about right and wrong.

Besides, the voice asked, what if there were a scenario where I was the weak one? In that circumstance, who would speak up for me?

The voice belonged to my mother, whose sense of what is good, just and compassionate has always been — and still remains — unshakable and unequivocal. With her, on moral issues, there is no negotiation. There is no convenient justification, served up courtesy of a political philosopher.

There is only right and wrong, and you had better know one from the other.

Having grown up in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, as the oldest of five children born to Tejano migrant farm workers with deep roots in the Lone Star State, my mother started working in the fields as a teenager in the 1950s.

Her family bounced between Texas and California for several years before settling in Sanger, a small farm town in Central California. My grandfather reluctantly pulled up stakes from Texas when he heard a rumor that the growers were paying $1 more per hour to pick fruits and vegetables in the Golden State.

While attending Sanger High School — from which I would graduate a quarter century later — my mom discovered poodle skirts, malt shops and Elvis. And, at a high school football game, she met my dad.

In November 1963, my mother was a student at Fresno City College, taking typing courses with plans to be a secretary or at least work in an office of some kind. It was there that she heard the unbelievable news that President John F. Kennedy had been shot and killed in Dallas. She recalls that Thanksgiving was sad that year, and for many years to come.

Five years later, as a working wife and mother chasing after her 1-year-old son, there would be more sadness with the death of Sen. Robert Kennedy — who was, more often, known around my grandmother’s house as simply “El Bobby.”

Also in the 1960s, on the East Coast, a suburban housewife and freelance writer published what would become a widely read book, challenging what was then the popular idea that women could find fulfillment only as wives, mothers and homemakers.

Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” is considered to have been extremely influential, and it is said to have played an important role in the creation of the modern feminist movement.

My mother missed the movement. After college, she went to work in an office and focused her efforts on what she considered her life’s most important goal: becoming a wife and mother, two roles that — along with being a good and attentive daughter — seem to have left her feeling quite fulfilled.

In 1972, Congress passed The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and sent the measure on to the states for ratification. The amendment — which declared that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” — died 10 years later when it failed to be ratified by 38 states.

The ERA didn’t mean much to mom. That same year, she had the last of her three children. Along with my father, she worked tirelessly — both inside and outside the home — to provide my siblings and me with a happy and safe upbringing. She couldn’t always help us with our homework, but she did help make us into good people who were taught to be kind and respectful to others.

That in and of itself is a fitting tribute to one of the women she most admired. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was fond of saying: “If you bungle raising your children, I don’t think whatever else you do matters very much.”

Whatever else my mom did, or didn’t do, in life, she did not bungle the raising of her kids. She got that right.

My mother is always the first to applaud what other women have done with their lives, the things they’ve accomplished and the barriers they’ve broken. She was “all in” for Hillary Clinton in two presidential elections.

It’s just that, in her case, more than money or fame, she counts the way her kids turned out as her life’s greatest achievement, even if my mom doesn’t always get the credit she deserves as a chief architect on the project.

My dad is the louder and more outspoken of the pair, and so he commands most of the attention. It’s a role that my mom is content to let him play.

We ask my mother a question, and often my dad answers. It’s annoying. But, within the family, it’s clear which one of them has more influence — over each other and over the rest of us.

All of which makes it harder to accept the reality that now, at 75, my mother is slipping away.

She forgets things — often. She repeats herself. She can’t remember if she ate or not. Her doctor is charting a “cognitive decline.” My grandmother, her mother, had Alzheimer’s, and my mom seems headed in that direction.

The woman who did everything for her kids now needs her kids to do more and more for her. It’s a privilege. And yet, it’s also heartbreaking to watch her slowly disappear.

In the upcoming film, “The Wife,” Glenn Close plays an invisible woman — if not literally, then at least figuratively. Her character represents generations of brilliant, hardworking and capable women who — because of sexism, tradition and societal norms — were, as the promotional material for the movie puts it, “relegated to supporting players in their own lives.”

In her life, my mom was no supporting player. She was performing at center stage, hemming costumes backstage, working lights in the control room, ushering people to their seats, selling popcorn in the lobby during intermission and doing a hundred other things that needed to be done.

It’s why I love the song “Mama” by the all-male quartet Il Divo. I sit alone and play it every Mother’s Day. The lyrics sum up what many of us would like to tell our mothers, and what the less fortunate never had the chance to tell them.

Mama thank you for who I am

Thank you for all the things I’m not

Forgive me for the words unsaid

For the times, I forgot

Mama remember all my life

You showed me love. You sacrificed

Think of those young and early days

How I’ve changed along the way

And I know you believed

And I know you had dreams

And I’m sorry it took all this time to see

That I am where I am because of your truth.

My sister — who didn’t have kids of her own, but instead now enjoys a hugely successful career and travels the world — reminds me that people make choices, that women make choices. She looks back on a former company, and notes that it’s no coincidence that most of the women managers who earned the highest salaries also had no kids.

Look at the data. Studies show that, for each child a woman has, her wages will decrease by about 4 percent. When a man has a child, however, his earnings increase by 6 percent. It’s completely unfair, yet totally believable.

Talk about wage inequality. There it is. Even when they re-enter the workforce after having children, some women will never catch up. Like my sister says, we all make choices.

My mom made her choices, and I hope she’s happy with them. For me, and for my siblings, her truth made all the difference.

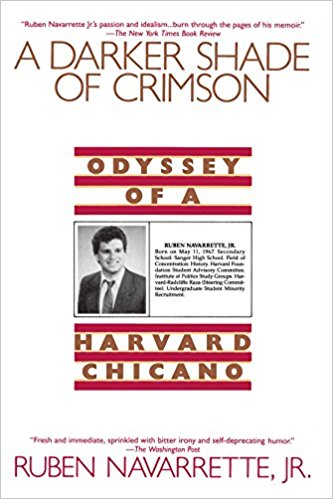

Ruben Navarrette, a contributing editor to Angelus News, is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a Daily Beast columnist, author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano” and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.”