Originally posted on Parts Unknown

Al Stehly has a clever reply whenever he’s in Sacramento, the state capital, and lawmakers from urban areas tell him they don’t have time to meet with him and, besides, they don’t have anyone in their district who farms.

“I tell them, ‘Do you have anyone in your district who eats?’” says Stehly. The organic farmer grows avocados, tangerines, and, most recently, wine grapes on 60 acres in northeastern San Diego County.

Stehly doesn’t fit the popular stereotype of a farmer; he wears tennis shoes, not boots; he drives an SUV, not a pickup truck; he went to college and studied business with plans of becoming an accountant or lawyer. But when his father, a farmer, passed away, he took over some of the crops—and kept planting. And thinking, and hustling; he’s always reading, researching, and looking for the next big thing in farming.

“Other farmers tell me, ‘Well, we’re surviving,’” he says. “No! We can’t just survive. We should be thriving.”

Spend five hours with Stehly in his fields, as I did recently, and you’ll get a revelation about modern farming — a thankless job that requires know-how, luck, and a steel spine.

You have to deal with politicians one day, and insects the next. Farmers would like less government regulation, but what they really need on a day-to-day basis are the essentials: good weather, affordable water, and readily-available labor.

It’s that last item that has brought me back into the fields. I grew up in farm country, born and raised around the fields in Central California, a lush region that supplies one-third of the U.S.’ vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts. Besides the agriculture—a $47 billion per year industry—you also have a good number of dairies and cattle ranches.

In my hometown of Sanger—a town of about 25,000 people east of Fresno—I was surrounded by trees that grew peaches, almonds, and oranges. There were also miles of vines that grew table and raisin grapes.

Only the grapes destined to be raisins or juice can be picked by machine. The machines are indelicate and often bruise the fruit they handle, making them unsellable to markets. But if the fruit—in this case, grapes—are going to be laid out in the sun for a few days to dry into raisins, it doesn’t really matter if they’re a little bruised.

There, now you know more about farm labor than most of the politicians in Washington.

In this country, one of the most profound divisions is the split between “The City Mouse” and “The Country Mouse.”

I’ve lived in a half dozen major cities: Boston, New York, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Dallas, San Diego. But, at heart, I’m still a country mouse.

So is Stehly. Several years ago I went to his farm to interview him for a column about the effect of the state’s drought on water-intensive crops such as avocados. On my first trip to his avocado grove several years ago, we mostly discussed water. We didn’t talk about labor at all; it wasn’t an issue at the time.

Back then, the president was Barack Obama. He virtually suspended immigration raids and instead sent employers threatening letters in the hopes that they’d purge their worker rolls of suspected undocumented immigrants. Obama also ratcheted up the practice of roping local police into enforcing federal immigration law. Over eight years, Obama set a record by deporting more than 3 million undocumented immigrants. Still, on most of the nation’s farms, it was business as usual.

Now, there’s a new sheriff in town. Besides pledging to overhaul the visa process to deny entry to legal immigrants who might need public assistance, President Donald Trump also promises a “big beautiful wall” on the 2,000-mile-long U.S.-Mexico border.

What concerns farmers like Stehly is Trump’s plan to create a new “deportation force” to remove the undocumented. Raids and sweeps are a real possibility. And while Trump has often tried to emphasize that he is focused on deporting so-called “criminal aliens”—the folks he calls “bad hombres”—it’s become clear amid detentions, arrests, and deportations that, in Trump’s world, the word “criminal” is broadly applied.

Agricultural workers are panicked, and farmers are nervous. There are stories about labor shortages and crops rotting in the field because workers won’t come into the open to pick them.

On the nation’s farms, there are still—and will always be—those crops that have to be picked or sorted by hand.

Stehly’s crops—avocados and tangerines—are like that. His wine grapes could theoretically be picked by machine, but you could never get one up the steep hill on which they rest.

So who does the picking? Almost exclusively Latin American immigrants.

There are a lot of myths, faulty assumptions and outright lies about farming. Here are two of them.

First, no matter what Trump says, or what the unions say, or what you hear on talk radio, Americans are not going to do these jobs—or at least not enough to meet the need. In the Central Valley, nearly all farmworkers are immigrants, and approximately 70 percent are working illegally.

Second, farm work is NOT unskilled labor. Come out to Stehly’s farm and have him take you into the avocado grove in search of the delectable tropical fruit. You’ll see farm workers who could moonlight as acrobats because they’re 10 feet off the ground, standing on ladders planted precariously on inclines (they help with irrigation). The workers have a heavy leather basket around their neck, and they’re using a “picking pole” to reach those avocados dangling far out on tree limbs. The pole has a trigger at one end, a blade at the other, and a basket tied to the bottom of it. While standing on top of the ladder, a worker pulls the trigger, the blade cuts the stem, the avocado falls into the bucket.

Anybody out there want this job? Stehly is hiring, and he’d love to have you. He doesn’t fit the unfair stereotype of the cruel grower who exploits the field hands. According to the workers I spoke to—many of whom refer to him as “Alberto”—he respects the essential role they play in keeping his livelihood afloat.

Stehly even pays more than minimum wage. In California, that is $10.50 per hour. He pays as much as $13.50 if you have experience. If you don’t know an avocado from an anchovy, he’ll still start you at $11.25 per hour.

C’mon, now. Don’t shove. Not everybody at once.

The absurdity is not lost on Jose Aranda, an undocumented immigrant from the Mexican state of Guanajuato who helps keep this place humming.

I break the ice by telling him, in my mediocre Spanish, that my grandfather came from Chihuahua as a child during the Mexican Revolution.

“I know Chihuahua,” he says with a half smile.

I also tell him I grew up around farms, and that I’m trying to find out what effect Trump’s proposed deportation force will have out here.

“It could cause a lot of problems,” Aranda says. “A lot of people are worried.”

Suddenly, he gets animated. He obviously knows the political backstory—that Trump and other politicians use deportations to supposedly open up jobs for U.S. workers.

“They say this is about work, that we’re taking work away from Americans,” Aranda says. “But work we have plenty of. They should come down here, and help us do some of it.”

The father of two bends my ear about politics in the United States and Mexico and laments how similar the politicians are in both countries.

“(Former Mexican president) Vicente Fox is like Trump,” he said. “They both like to talk. That’s all they do.”

Aranda adds that even though he disagrees with Trump on Americans losing jobs to immigrants, he also agrees with some of what Trump wants to do—like deporting criminals and battling the Mexican drug cartels.

To stay on top of and contextualize current events on both sides of the border, he reads Mexican newspapers and skims biographies of former U.S. presidents at his public library.

Aranda says he has no legal documents. The first time he crossed the border was about 13 years ago, he says, and he paid a coyote (smuggler) $3,500 for the privilege of risking his life on a long, hard journey that some don’t survive. He returned to Mexico three years later after which he paid $4,500 to get back to the United States so he could earn money for his family, who stayed in Mexico. The next time he goes back, he’ll stay. Now it’s too hard, and expensive, to cross.

Finally, I ask about his family. He boasts that he has two daughters, 13 and 18, in private school in Mexico, and that they’re learning English.

I ask, when did he see them last?

He gets quiet. After a brief pause, he says that it was on his last trip to Mexico—10 years ago. His eyes moisten.

This man missed his daughters’ entire lives. All so they could have better ones.

What kind of parent does that? A good one. Are these the people we’re supposed to be afraid of? Are these the “bad hombres” that Trump warns us about?

If farmers like Stehly, who can’t use machines, had to rely on American workers to harvest their crops, they’d go out of business. We’d lose tax revenue, farm towns would dry up, and good luck finding your favorite fruit or vegetable in your local supermarket. Whatever you found would be three times the price, and half the quality, because it would have been imported from outside the U.S.

But what about the idea that farmers could somehow survive a series of Trump raids, and that agriculture really isn’t as dependent on undocumented immigrants as many farmers claim?

That’s a substance with which farmers like Stehly are very familiar. They use it to fertilize crops. It’s called manure.

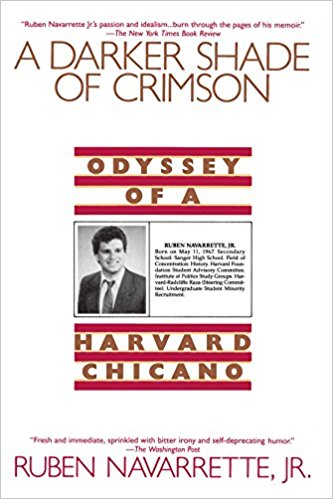

Ruben Navarrette Jr. is a nationally syndicated columnist with the Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a columnist for The Daily Beast, a commentator on radio and television, a popular speaker, and author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano (Bantam).” Follow him on Twitter @RubenNavarrette.