For my father, it all started with a children’s book depicting a cat stuck in a tree.

Once a cop, always a cop. My dad was on the job for 37 years, and — although he’s now retired — he’ll remain a cop until he draws his last breath.

The book in question was from a series that was popular in the 1950s and 1960s. The main characters were two children named Dick and Jane, and they had two pets: a dog and a cat. One day, the cat climbs up a tree and a friendly neighborhood policeman helps get it down for the kids.

My dad was sold. That’s it, he thought to himself. He decided to be a policeman, so he could help people.

Now I hear, courtesy of National Public Radio, that police departments around the country are having an extremely tough time recruiting new officers. In fact, in many cities in America, tough has become more like “nearly impossible.”

There are many reasons that recruiting cops has become so difficult in so many places.

But let’s get something straight right off the bat: Salary is not one of those reasons. Today, police officers often earn a comfortable living. And when they retire, many of them wind up with a generous pension and lifetime health benefits.

Over the years, current and former law enforcement officials have told me that one factor that hurts recruitment is a dried-up pipeline from the military. From the 1970s to the 1990s, they said, police departments could count on recruiting people who had just been discharged from the military. Then came the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and America found itself on a constant war footing that has continued to this day. Suddenly, the military isn’t so eager to discharge the people it has spent years and millions of dollars training. That leaves police departments out of luck — and looking for warm bodies elsewhere.

Also, the last five years have been brutal for the public image of law enforcement. Ever since the shooting of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson in August 2014, and the riots that followed — and the scattered shootings of police officers, seemingly in revenge — an already difficult and thankless job has become more difficult and more thankless.

You can’t blame millennials for not wanting to go within a hundred miles of a gig like that.

Some police departments have stooped to poaching prospects from departments in other parts of the country. Others are tweaking the marketing process to help their chances of appealing to young people who grew up in an area where police are often seen as bullies and provocateurs.

This subject weighs on the mind of Bob Harrison. Having been on the job for more than 30 years, and served chief of police in a number of California cities, Harrison has also studied business strategy at Oxford University and worked as a researcher for the RAND Corporation.

He now spends his time training the law enforcement leaders of the future. As a faculty member and course manager for the CA POST Command College, he runs weeklong programs in the San Diego area that allow those in middle management to gain the additional skills necessary to lead departments.

I asked Harrison why he thought it has become so difficult to lure recruits into law enforcement.

He cites a pair of factors: a decline in what used to be called “community policing” and the failure of many departments to do effective public relations.

“We don’t have a recruitment problem,” he told me. “We have an attraction problem. Most people want to respect and have confidence in the police but the police don’t think about building bridges back to the people.”

For him, the whole concept of policing boils down to simply lending a helping hand when people need it most.

“If I have the worst day of my life, I want to know that someone shows up,” he said.

In the last half century, police officers have gone from guardians to warriors to social workers.

“People say, ‘Well, I’m a cop, not a social worker,’ ” he said. “Sadly, you’re both. Because, at that moment when this person’s life is blowing apart, you’re the only one there.”

Wise words. At our most stressful moments, cops are often not just the first ones there. They’re the only ones coming.

Police departments need to do everything they can to get recruitment flowing again and keep officers on the street.

This starts with something that turns out to be my line of work: telling a good story. In this case, the story that needs to be told is the story of policing.

If the public understands why the police are so important, more people will step forward to fill that role.

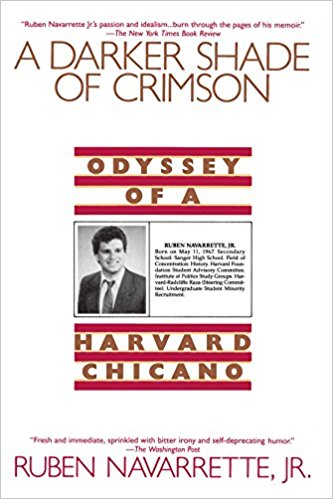

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”