Confronted with heart-wrenching images of children snatched from parents at the U.S.-Mexico border, good people will feel as if there is nothing one person can do to make their sliver of the world a kinder and gentler place.

“First is the danger of futility,” Kennedy told his audience. “The belief there is nothing one man or one woman can do against the enormous array of the world’s ills — against misery, against ignorance, or injustice and violence. Yet many of the world’s great movements, of thought and action, have flowed from the work of a single man.”

One such man is Richard Villasana, a bi-national guardian angel who works to spare children the pain of family separation.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents often add to the pain. In El Paso, Texas, on Christmas eve, ICE agents played Scrooge by dumping hundreds of asylum-seekers in the parking lot of a bus station.

Villasana hates the thought of thousands of children being funneled into foster care. And whether those children come to the United States as unaccompanied minors or with parents who wind up incarcerated or deported, foster care is where many of these would-be refugees wind up. When they turn 18, they’re released into the streets — with no family, no home and no hope. The first time they run across a predator, they wind up on the menu.

But not if Villasana can help it. As the founder of a nonprofit organization called Forever Homes for Foster Kids, he spends his days trying to locate relatives of some of these children in the hopes that the kinfolk will take in these kids and get them out of the foster system.

What a great idea. Simple but effective.

But there is a catch. Not just anyone can do this magic trick. We’re talking about tracking down people in Third World countries with scant personal information to go on. Locating someone in the Mexican state of Oaxaca is not like finding someone in Ohio.

Luckily, Villasana has a knack for finding people by putting information together, using just phones and people skills, following a paper trail and analyzing data until the bread crumbs lead to an aunt, cousin, grandma or parent.

“You gotta remember, when I started, I was doing all this pre-Google,” he told me.

Born in Houston and raised as one of nine kids, the Mexican-American Villasana at first had no use for hyphens. “I thought of myself as American growing up,” he said. “I wouldn’t think of being Mexican until many years later.”

It was also years later that he’d learn to speak Spanish. His parents remembered well the bigotry and racism they experienced as children, he said. And they didn’t want their kids to experience the same sort of thing. Now Villasana speaks four languages — Spanish, English and some Italian and French.

He left for Desert Storm with the Naval Reserves in 1989 and later relocated to San Diego. There, he developed an international consulting business that required him to often cross the border into Tijuana. His specialty: helping US companies do business in the Mexican medical field. You have to do and say the right thing to open doors in a foreign country.

Villasana learned a lesson that seems to have eluded the person in the Oval Office: South of the border, you get more with honey than with vitriol. Before long he was known as “The Mexico Guru” and giving seminars about doing business in Mexico. He even wrote a book, “Insider Secrets for Doing Business in Mexico.” I asked him to share one of those secrets.

“Whether you speak Spanish has nothing to do with it,” he said. “The key is knowing how to talk to the Mexican people, including the Mexican government. If you approach them with respect, it puts them at ease. And they want to help you.”

Reuniting children with family is a labor of love, with an emphasis on the “labor” part. The organization operates in the red.

“This is dogged work,” he said. “It’s hard, and it’s depressing. But I keep going because I know that on the other end of this long road is a child who needs help.”

This is a good man — just the kind of person we need when things on the border are so bad.

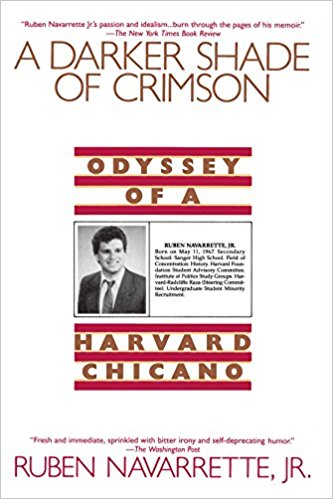

Email Ruben Navarrette at ruben@rubennavarrette.com.