What does it mean to be Mexican-American?

A few years ago, a regular reader of my column sent me an email that contained this gem: “You write like a Mexican, you need to write like an American.”

If he only knew what a hornet’s nest he was stirring.

You see, around my house — with my Mexican-born wife, and me born in the United States to parents who were also born here — the issue of whether one identifies as a “Mexican” or an “American” has more ingredients than the recipe the Mayans handed down for mole. And the conversations can be just as spicy.

The chasm between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans isn’t often talked about in mixed company. But take it from me, it’s real. And the struggle is real too. Heritage and ethnicity are fine. But nationality counts for a lot.

Consider what I often refer to as my “mixed marriage.”

My wife is a legal immigrant from Mexico who came to the United States as a child and became a U.S. citizen. She speaks, writes, and reads both English and Spanish fluently. At heart, she considers herself Mexican. You know what they say: You can take the girl out of Guadalajara, but you can’t take Guadalajara out of the girl.

Well, if they don’t say that, they should.

For my part, I’m a Mexican-American Yankee Doodle Dandy. Born in Fresno, California — and raised nearby in a small town called Sanger — I have always viewed the world through the eyes of an American. Mexico is a foreign country where I never feel totally comfortable. It might as well be Belgium. I speak Spanish, but, when I do, I’m usually self-conscious.

And like most husbands, I’ve been known to say things that my wife contends are dumb even ridiculous.

About ten years ago, when watching a news report about Mexicans protesting their government, I channeled Thomas Jefferson and said something like: “Well, why don’t people just organize and replace it with a government that works better?”

My wife shook her head and said: “You’re such an American. You think anything is possible, and change is easy. Yeah right! This is Mexico. The people there have no power.”

I shrugged and changed the subject.

Even our taste in food is different. My wife could eat ceviche and enchiladas every day of the week, while I’m just as partial to hamburgers and hot dogs. And when we do manage to agree on one kind of food, there are still cultural variations in how we expect it to be prepared. Growing up, my idea of what a taco looked like was a hard shell, ground beef filling, lettuce, tomato and cheese. My wife is horrified by the mere thought of such a thing. For her, a taco is a small corn tortilla with meat, onions, and cilantro served open face. Anything else is what “gringos” eat.

And yet I like to think I’m not completely whitewashed. In fact, I cling to my hyphen.

Don’t misunderstand. I have no beef with those Americans of Mexican origin — a group numbering about 30 million in the United States — who think of themselves simply as “American” or, at the other extreme, as “Mexican.”

But I want to have my flan and eat it too. I like my hyphen. I’m a Mexican-American. Though at times, to be honest, I do feel more like an American-Mexican. There is a difference, you know. It comes down to how you see yourself. I have friends who consider themselves half-American, half-Mexican.

Wait, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s not put the cart before the burro.

When the reader accused me of writing “like a Mexican,” I had to stop and wonder what that meant. I imagined myself in a sombrero and serape, pecking away at my laptop with a burro named “Pepe” at my side.

Of course, I know what he really means. He had obviously just read a column I’d written on immigration, one that he probably disagreed with. He attributes his views to the fact that he considers himself a red-blooded, clear-thinking American. And since we disagree, and I have a Spanish surname, that must mean that I’m less American than he is, and that my true loyalty lies with Mexico. Ergo, as far as the reader is concerned, I write “like a Mexican.”

It wasn’t really about how I looked or dressed. It wasn’t even about what language I spoke. It was about my national fidelity, my world view, my frame of mind, my love for America.

The reason for the hornet’s nest has a lot to do with a subject that baffles many Mexican-Americans: identity.

Several years ago, on a trip to Mexico City, I had just made my way down the concourse at Benito Juarez International Airport and arrived at the immigration processing area when I got stumped by what should have been a simple question.

Signs pointed to two lines: for “Mexicanos” (“Mexicans”) and “Extranjeros” (“Foreigners.”) I stood there for a few seconds, unsure of where to go. Growing up in the brown-and-white world of Central California, I had been called a “Mexican” my entire life. But I feel 100% American, especially when I’m on foreign soil. Hence, “Mexican-American.”

After a few minutes of indecision, I took my U.S. passport and discreetly got in the line for Extranjeros.

Here’s where the story gets weird. Long before I met my wife, while I was growing up in Central California, I never considered myself anything but a Mexican. Not a Mexican from Mexico, like my grandpa who was born in Chihuahua and came here as a child with his family. But a Mexican living in the United States.

Just as importantly, it was how, it seemed, others saw me and people like me. Adults referred to the “Mexican” part of town or bragged about the high school’s first “Mexican” quarterback or first “Mexican” homecoming queen.

During my senior year in high school, when I was admitted to Harvard, jealous white classmates kindly informed me: “If you hadn’t been Mexican, you wouldn’t have gotten in.”

Note: They did not say Mexican-American. Just Mexican. It’s ethnic shorthand.

Even today, many of my readers take the cue. Years ago, one accused me of supporting “the Mexican invasion … because you’re Mexican.”

OK, so we’re back to that? Now I’m Mexican — again. Just like my friends in Boston call themselves Irish, and my friends in New York call themselves Italian, and my friends back home in Fresno refer to themselves simply as Armenian.

I’m Mexican, right?

Wrong, my wife insists. Many years ago, when we first started dating, she was on the phone with an old friend from Mexico who asked about me. “He’s American,” she told her friend.

I was offended. “Why didn’t you tell her I’m Mexican?” I asked her later.

She laughed and said, “If I had done that, she would have asked me what part of Mexico you were from. And I would have had to have said, ‘Fresno.’

Good point.

The whole story reminds me of the old saying that a Mexican-American is seen as an “American” everywhere in the world except America, and a “Mexican” everywhere except Mexico.

That’s me. I’ve spent my entire life feeling a little too Mexican to be 100% American and a bit too American to be 100% Mexican. I’m a man without a country. And yet I feel firmly rooted in one country, and faintly connected to another.

But it’s when I go to Mexico and encounter the “elites” — who essentially ran my grandfather and his family out of their own country by not providing enough opportunities to stay — that things get really interesting. We’re like oil and water. Nothing unites us but mutual contempt for one another.

I’ve always thought it odd that aggrieved Mexicans in Mexico can remember every detail of the American land grab in 1850. Yet they’re hazy on how people like them have abused and neglected other Mexicans at least since the Mexican Revolution, which occurred more recently from 1910 to 1920.

To think that there are nativists in the United States who believe that Mexican-Americans are in cohorts with our distant relatives to the south to retake the Southwest in a planned “reconquista.” What is wrong with some people?

Comically, some of the cultural tension between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans was captured in a memorable scene in the film, “Selena,” a biopic about famed Tejano music sensation, Selena Quintanilla. The singer’s father, Abraham, who was played by Edward James Olmos, talks about the difficulty of being too much of one but not enough of another.

“Being Mexican-American is tough. Anglos jump all over you if you don’t speak English perfectly. Mexicans jump all over you if you don’t speak Spanish perfectly. We have to be twice as perfect as anybody else…We must know about John Wayne and Pedro Infante. We must know about Frank Sinatra and Agustin Lara. We must know about Oprah and Cristina…We must prove to the Mexicans how Mexican we are. Prove to the Americans we’re American. We must be more Mexican than Mexicans, more American than Americans…both at the same time! It’s exhausting.”

You bet it is. No wonder that — when my wife corners me after one of our cultural skirmishes and puts me on the spot with a pointed question — I’ll be glib, if it will shut it down.

“Exactly what kind of Mexican are you?” she’ll ask.

With a smile, I respond, “The American kind.”

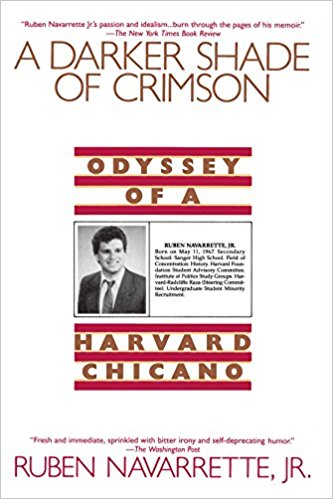

Ruben Navarrette, a contributing editor to Angelus News, is a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group, a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors, a Daily Beast columnist, author of “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano,” and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.”