As many Americans have likely figured out by now, immigration is by far the most divisive issue in the United States.

In fact, in speeches, I often refer to it as the most divisive issue that Americans have had to contend with since slavery.

The immigration debate divides our country — by race, class, geography, ideology, profession, ethnicity, national origin, etc.

It divides neighbors, friends, coworkers, and family members. It divides those who can sympathize — or even, if they’ve been there, empathize — with immigrants from those who cannot. It divides those who are a generation or two nearer their immigrant ancestry from those who have totally assimilated and melted into the pot.

The immigration debate certainly divides the political parties. If you watch a video of how Republicans and Democrats talked about immigration in 1980, you’ll see that it’s pretty much the opposite of how the parties talk about it today.

Back then, Republicans supported the free flow of labor and went to bat for the undocumented as hardworking individuals who deserved a shot at a better life; Democrats pushed protectionism, keeping out illegal immigrants and preventing those who were here from being legalized to protect U.S. workers from the horrors of competition.

It divides Americans based on the different realities they see when they turn on the television and view images of thousands of refugees mixed with migrants showing up uninvited at the U.S.-Mexico border near Tijuana.

Some people see those images and think the country is being invaded by predators and takers who want to impose their culture and language on the rest of us; others see desperate human beings who simply want to provide a better and safer environment for their children, and they are willing to sacrifice everything and work their tails off to obtain it.

It divides those who want a genuine, workable, and long-term solution to the immigration problem — that is, if Americans can even decide that there is a problem — and those who prefer simple solutions that fit on bumper stickers with room left over, like “Close the Border” or “Build the Wall” or “Deport All Illegals.”

Finally, it divides those who are brave enough to hear uncomfortable truths about why people migrate from one country to another, and what can be done to better control the process, from those who prefer to hear untruths that are easier to digest.

You see, there isn’t much truth in the immigration debate. Politicians lie about immigrants, and about the opposition. Republicans talk tough and govern soft, while Democrats talk soft and govern tough.

But let’s slip the bonds of provincialism for a moment and think globally. The division wrought by immigration doesn’t stop at the borders of the United States. The debate also divides many countries. The curious part is that, in country after country, the fault lines seem oddly familiar.

Look what’s happening in northern Mexico, where thousands of Central American migrants and refugees have gathered after abandoning their homes and traveling hundreds of miles in search of better lives, safer surroundings, and brighter futures.

You would think that Mexicans — who are constantly on the move to the United States for similar reasons — would, of all people, have empathy and compassion for their displaced neighbors.

Sadly, many Mexicans didn’t react that way. In fact, they reacted horribly. The televised images coming out of Tijuana were jarring — and depressing. Angry mobs protested against the refugee caravan, and what they saw as the Mexican government’s policy of coddling the invaders and encouraging them to stay.

Do you suppose the Tijuana mob wanted to drive out the migrants in order to “Make Mexico Great Again”?

Maybe the Mexican government did want some of the refugees to stick around. Maybe get a job. There are several thousand unfilled manufacturing jobs in Tijuana, with no Mexicans to fill them. Many of the able-bodied work in auto plants that pay higher wages, or head north to the United States with the help of smugglers.

At a recent job fair in Baja, California, house painters, welders, and construction workers from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador lined up to fill out applications for jobs that would keep them planted in Mexico for the foreseeable future.

So much for the claim — advanced by some — that the refugees are just coming north looking for welfare and other handouts. Turns out many just want to work.

Meanwhile, in the United States, one of the more insidious proposals, championed by the Trump administration, is to let people into the United States based on education and skills.

So, in other words, let’s run the U.S. immigration system like an Ivy League admissions office? That’s a terrible idea. Imagine the talent that would fall through the cracks.

In deciding who should be allowed entry, in most countries, prejudices come into play. Favoritism is a given. So is fear.

Whether we’re talking about Great Britain, Spain, Israel, Italy, Greece, or Canada, many people worry that immigrants change demographics, lower the standard of living, drain social services, and put a strain on jails, schools, and hospitals.

In fact, when it comes to immigrants, countries all over the world have the same national motto: “There goes the neighborhood.” And which of the world’s neighborhoods is earning a reputation these days for struggling with immigration? The winner is Europe.

That point is not lost on Hillary Clinton.

In her own public career in the United States, Clinton mastered the art of having it both ways on immigration, alternating between hard and soft. One minute, she would pander to white voters in the suburbs by declaring on a New York radio station, in 2005, that she was “adamantly against illegal immigrants.”

The next, she was pandering to Latino voters by criticizing the Trump administration’s policy of separating immigrant families and pledging to support a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants.

Now, in a recent interview with the Guardian, Clinton advised Europe to “get a handle on migration” because that is the one issue above all others that helped light the fire of right-wing populism. She called upon the leaders of European countries to send a strong signal that they will no longer “provide refuge and support.”

The former secretary of state did praise German Chancellor Angela Merkel for being “very generous and compassionate” in welcoming Syrian refugees into her country, even though the policy seems to have ended her political career. Yet, she suggested, lenient immigration policies had caused troubling developments, including Great Britain’s decision to leave the European Union — and, in the United States, the election of President Donald Trump.

Finally, Clinton warned, “If we don’t deal with the migration issue, it will continue to roil the body politic.”

That’s where she lost me. I’m all for “dealing with” the migration issue. But I don’t see how skirting the topic by keeping out migrants helps you deal with it.

I also don’t understand how the centrists — if that is what Clinton is trying to be this week — expect to battle the populists if they only make them stronger by giving in on immigration. Capitulation on such an important issue only empowers the “Britain First” or “Italy First” or “Greece First” crowd.

In any case, what Clinton said brought back memories for me. I remember the exact moment when I realized that other countries all over the world were dealing with the same pressures due to immigration as the United States — and making the same mistakes.

Nearly 10 years ago, I found myself sitting around a conference table in Lake Como, Italy. A mixture of journalists and policymakers had been invited there by a Washington-based think tank to discuss the migration policies of the United States — but also the half dozen other countries represented at the table.

Our friends from Canada worried that immigrants from the Middle East were segregating in their own neighborhoods and not assimilating as fast as their hosts would like.

An editor from a newspaper in Spain talked to me about the curious reverse colonialization of immigrants from Colombia and Peru finding their way to Madrid and Barcelona.

Israelis used to hire Palestinians to clean their homes, until one of the Intifadas made them fearful and sent them looking for replacements. They found them: Southeast Asians.

The countries and languages were different, but the pattern was the same. People from country X decide they have no interest in doing their own chores, or perhaps they’ve lost the ability to do them effectively. They hire immigrants from country Y, but instantly consider them inferior — in part because they’re willing to do the dirty jobs.

They also resent the newcomers for doing work they wouldn’t do, and doing it better than they could ever do it. They don’t exactly welcome the migrants into their mainstream but force them — directly or indirectly — to gather in what evolve into ethnic neighborhoods. With everyone sticking to themselves, ignorance thrives and stereotypes flourish.

The universality of the immigration debate makes perfect sense when you think about where it draws its fuel.

I’ve written about this discussion for three decades. And — when it comes to what drives it — I have a fairly good idea of how the pie chart breaks down.

I’d dedicate 10 percent each for legitimate concerns over rule of law, public safety, the strain on public services, territorial sovereignty, and changing demographics. The other 50 percent, I would estimate, is an illegitimate mixture of racism, nativism, hatred, condescension, and fear.

The ingredients in that toxic cocktail are part of human nature. And human nature is an international phenomenon.

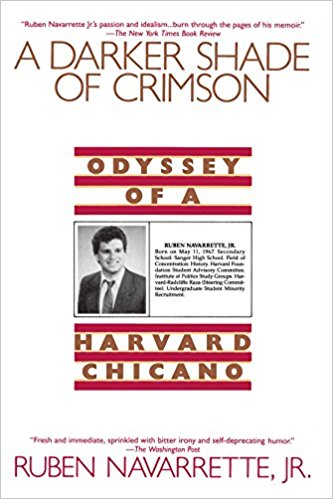

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”