Lately, I’ve been asked more than once to share my insights about how to reach and teach Latino students and ensure that America’s largest minority fulfils its academic potential.

The question is urgent because of math. Latinos account for 25 percent of the average kindergarten class, just as they are likely to account for a quarter of the U.S. population by 2030. If that cohort isn’t sufficiently educated, it’ll be stuck in low-wage jobs and contributing less in taxes than they would if they had better-paying jobs. Shortchanging these students could eventually short-circuit the country’s entire economic system.

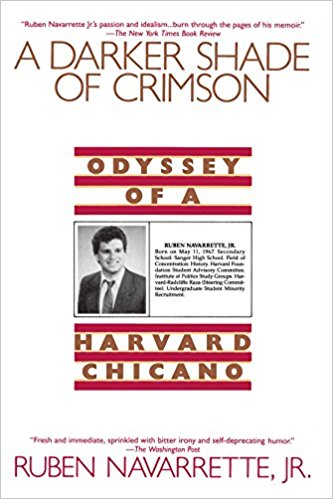

For the answer, I tapped into three things: my own experience as a high-achieving, self-starting Mexican-American student who made it from a small, mostly Latino farming town in Central California to Harvard; what I’ve studied, been told, and learned over the years about K-12 education, including what I’ve seen on the front lines as a substitute teacher in my old school district; and what I’ve gleaned from interviews with teachers, principals, and superintendents about what they’re doing to help educate a student population that has often been difficult to inspire.

From my experience, the formula for turning out hard-charging Latino academic superstars starts with the education triangle. At one corner, you have the student — who has to be in class every day, and ready to work hard and follow the teacher’s commands. At the second corner, you have the teacher — who knows the material but also how to communicate it, and who knows that students learn in different ways and adjusts accordingly. And at the third corner, you have the parent who supports both student and teacher, and makes sure that both get what they need to make the magic happen. Everyone works together, or none of it works.

Given what I saw on the front lines, we need high goals, strict accountability, regular testing, flexibility in the curriculum, rigorous academics, high standards, and an end to making excuses about which groups kids can learn and which groups can’t.

The excuses game can easily descend into racism and classism, where we write off whole categories of students as not being educatable and thus not worth the effort. We used to blame the bloodline, then the culture, then the parents. Now we blame the environment, or socio-economic status. But the goal is always the same — to let the public schools and those who work in them off the hook for failing some students due to what former President George W. Bush called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Finally, judging from what educators tell me, there’s a lot more that Americans could be providing our public schools to make them more effective. And I’m not talking about more funding.

One teacher told me that there needs to be more of an emphasis on early childhood reading at the K-3 level, those all-important years that set the tone for the rest of the student’s education. He also said there needs to be more counseling, and not just the academic kind. Students can face a variety of traumas that get in the way of learning. We have to deal with those.

A district administrator pleaded for more flexibility in how schools can spend their budget allotment and more power to hire teachers on an individual basis instead of through a collective bargaining process that sometimes gets in the way of efficiency. Schools exist for the convenience of the adults who work in them, and not to serve the students who attend them. Can’t we do both?

And lastly, a retired principal insisted on strict accountability across the board so that teachers and administrators alike are held responsible for how well students perform in every class they take. He also suggested that — in return — we pay teachers more and work with banks to provide them with low-interest home loans.

They were all trying to send the same message: Educating our students is too important to be left only to the educators. The academic health of our children is everyone’s business, and so it needs to be everyone’s responsibility.

As you can see, there are plenty of ideas about how to do a better job of educating Latino students. We don’t need more studies, commissions, and policy directives. We just need the courage to confront our prejudices and the will to do what we know needs to be done. We need to hold people accountable, and expect more from students, teachers, and parents.

We could also need to recognize that much of what we’ve been doing over the last few decades has not worked and that it is time to try something new. It’s time to put the focus where it belongs: the schools. If we improve what goes on there, Latinos students can go anywhere.

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”